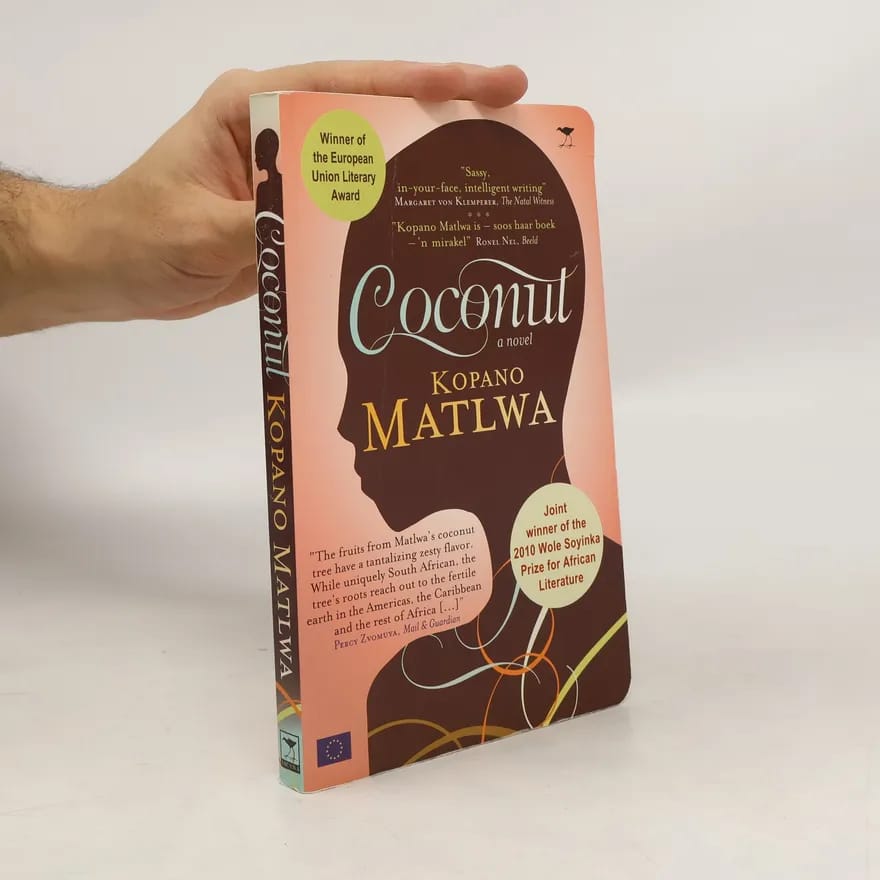

Matlwa’s debut novel slices into the glossy façade of post‑apartheid South Africa, following two black girls whose lives expose the hidden costs of chasing whiteness. Pictures Credits: Book bot

By Duncan Mnisi

Book Review – Kopano Matlwa’s Coconut is a brief but punchy novel that reads like a series of diary entries from two very different Black girls growing up in South Africa’s so-called “new” democracy.

Ofilwe, the daughter of a newly wealthy BEE beneficiary, lives cocooned in a white suburban world of private schools, shopping malls and social expectations shaped by whiteness. Fikile — who renames herself “Fix” — scrapes by in a cramped township, hustling for survival while dreaming of a glossy, Westernised life pulled straight from the magazines she devours.

Through their alternating voices, Matlwa exposes the painful contradictions of the “coconut” label — Black on the outside, white on the inside — and interrogates whether South Africa’s post-1994 freedom truly dismantled colonial mindsets, or merely repackaged them.

Matlwa’s language is deliberately simple and sharp. She writes in short, blunt sentences that echo a teenager’s inner monologue, giving the novel an urgent, confessional tone. As one Goodreads reviewer observes, “The author doesn’t hold back with the punches. The characters are full of faults and humanity.”

By placing Ofilwe’s privileged suburb alongside Fikile’s impoverished township, Coconut highlights the enduring economic divide that continues to follow racial lines. South Africa remains one of the most unequal countries in the world, with the top 10% holding around 71% of the nation’s wealth (World Bank, 2023). Matlwa’s storytelling feels like a literary snapshot of that stark reality.

There is also a sharp satirical edge. The title itself is a tongue-in-cheek but cutting label for Black people perceived to be mimicking white culture. As one reader puts it, “A ‘coconut’ in South Africa is what the US calls an ‘Oreo’ — black outside, white inside.”

More than two decades after apartheid, the so-called “born-free” generation is still wrestling with questions of identity, class and belonging. Coconut remains a powerful mirror for South African youth, forcing readers to ask whether the freedom promised in 1994 is genuine, or simply a polished veneer. As one scholar notes, the novel “highlights the fault lines that persist in contemporary South African society.”

Coconut is a quick, eye-opening read that delivers its critique without preaching. Its fragmented, vignette-style structure may feel plotless to some, but that is precisely its strength — capturing the messy, unfinished business of a country still learning how to love its own skin.