Is South Africa the Lackey of World Superpowers?D

By Thulane Madalane and Dipitsi Pitlo

Cape Town:In 2009, the South African government made the controversial decision to deny a visa to the Dalai Lama, preventing him from attending a Nobel Laureates’ peace conference in Johannesburg. This decision ignited widespread criticism, with many believing it was made under pressure from China, a vital trading partner for South Africa that regards the Dalai Lama as a separatist. Initially, the South African government claimed that the visa denial was intended to avoid distracting attention from the 2010 FIFA World Cup. However, this explanation was met with skepticism.

The Dalai Lama faced additional visa delays in 2011 when he intended to attend a birthday celebration for Archbishop Desmond Tutu, another Nobel laureate. A South African court later ruled that the government’s officials had acted unreasonably in delaying the visa decision, further hinting at the influence of Chinese pressure. This begs the question: Is South Africa a sovereign state, or has it become a lackey of world superpowers?

Donald Trump’s return to the White House followed a four-year gap during which he lost the election to his fierce competitor, Joe Biden. Trump’s comeback was bolstered by significant financial support from Elon Musk, who reportedly donated $288 million to Trump’s campaign, according to the Washington Post. This substantial contribution granted Musk considerable sway over the new administration, leading to concerns about the degradation of presidential authority, with reports suggesting that both the President and his Cabinet received instructions from unelected individual who happen to be Mr Musk.

During this time, the U.S. government halted donor funding to numerous countries, including South Africa. Moreover, Musk pressured the South African government to grant his global broadband internet access company, Starlink, a license without adhering to local legislation, such as the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) regulations. When his request was vehemently rejected, Musk took to social media platform X to propagate falsehoods, claiming, “Starlink is not allowed to operate in South Africa because I’m not black.”

In response, Clayson Monyela, a senior official in South Africa’s Department of Foreign Affairs, emphatically refuted Musk’s claim on social media. “Sir, that’s NOT true & you know it! It’s got nothing to do with your skin color. Starlink is welcome to operate in South Africa, provided there’s compliance with local laws,” Monyela wrote, emphasizing the principle of global trade and investment.

Musk’s claims resonated with AfriForum, an Afrikaner pressure group, which traveled to the U.S. capital to echo Musk’s narratives regarding local legislation such as BBBEE and the Expropriation of Land, both aimed at empowering historically disadvantaged groups. In January, President Ramaphosa signed the Expropriation Bill into law after extensive parliamentary debate, despite opposition from the Democratic Alliance (DA) party. The law permits the government to seize land from any private owner for public purposes, ensuring fair compensation but allowing for confiscation without compensation in certain instances.

Some Afrikaner groups worry the new law may lead to violent land confiscations, adversely affecting property values. The Trump administration has alleged that South Africa’s white minority is being unfairly targeted—an assertion robustly dismissed by the government in Pretoria.

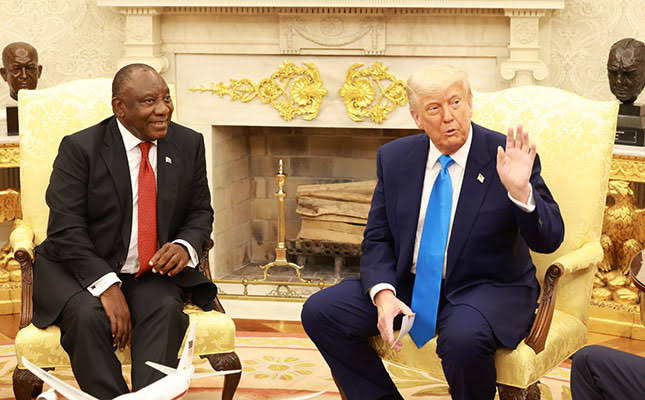

On the May 2025, 49 Afrikaners, including families and small children, arrived in the U.S. after Trump issued an executive order accusing South Africa’s Black-led government of racial discrimination and announcing a program to offer them relocation to the United States. In a meeting with Ramaphosa on Wednesday, Trump remarked, “We have many people that feel they’re being persecuted, and they’re coming to the United States.” He specifically referenced white farmers as being victimized.

Ramaphosa, remaining poised, countered Trump’s claims about racial violence, noting, “If there was Afrikaner farmer genocide, I can bet you these three gentlemen would not be here,” referring to prominent white golfers present in the room. Billionaire Johann Rupert supported Ramaphosa’s position, emphasizing that crime affects all South Africans.

After the meeting, Ramaphosa shifted the focus towards trade, highlighting discussions about critical minerals in South Africa. He also pointed out the government’s proposal to purchase liquefied natural gas from the U.S. However, he firmly denied Trump’s allegations regarding widespread racial violence against white farmers. Rupert insisted that South Africa needs technologies like Starlink to combat crime effectively.

The question remains: does the South African government prioritize diplomacy over accusations and disrespect? Initially, it was China instructing Pretoria to deny the Dalai Lama a visa; now, it is Donald Trump advising the South African president on how to govern his country. Has South Africa become subservient to the demands of world superpowers? Why does South Africa continue to beg for assistance? The U.S. has over 600 companies operating in South Africa, while South Africa has only 22 companies in the U.S. Why can’t the government impose stringent regulations on multinational corporations looking to do business in South Africa to ensure that local interests are prioritized?

As South Africa navigates its position on the global stage, these questions merit serious consideration.